Teaching adults is a particularly rewarding endeavor. Adults are goal-oriented and self-motivated students with a lifetime of interesting stories and experiences to share. Your job as an instructor might be to lead your learner into a better future as they use their new-found skills to obtain a better job. Or perhaps your purpose is to reduce isolation and connect less-mobile seniors with friends and family through social media.

Your role as an instructor is critical. Your challenge is to meet the needs and expectations of each unique classroom by adapting instructional material in ways that make it relevant to the students in front of you. When I write instructional material, I have to make work for a bunch of partners: the job training center in Texas, the library system in Florida and California, the engaged adult and the lifelong learner in a senior center. I am not in the classroom, my job is to document as many of the possibilities as I can for the myriad of learners and teachers who will use my materials. I rely on you to make it relevant to a classroom of learners.

In this series of posts I’ll talk about cognition–how we think and learn as it relates to the best practices of teaching adults and seniors, and the older group I will call the “older old.” For our purposes, I’m drawing a distinction between adults and seniors (over 60?) and older adults and those who are beginning to exhibit MCI (mild cognitive impairment). You may have heard a lot about older adults and learning. You may have heard that old dogs can learn new tricks. In this series, you’ll learn that not only can they learn new tricks, but sometimes they can actually out-perform young-uns! Let’s start with a overview of cognition and learning.

How do we learn (make new memories)?

Science tells us a lot about how we learn new things. First, we take in stimuli with our eyes and ears. That sensory information is processed by the brain and temporarily put into working memory. Your working memory is a busy place. It is where your consciousness resides. Incoming information is considered, evaluated, and combined with memories retrieved from long-term memory. If we are successful at learning (information transfer), we encode new information to our long-term memory.

Here’s the rub. Working memory can’t hold much. For instance, you can only hold about 7 numbers in your head for more than a few seconds, and that’s if you can concentrate and aren’t distracted. To successfully commit, or encode, new information to long-term memory, you need to use it, or think about it deeply during its short time in working memory.

Overload and fatigue

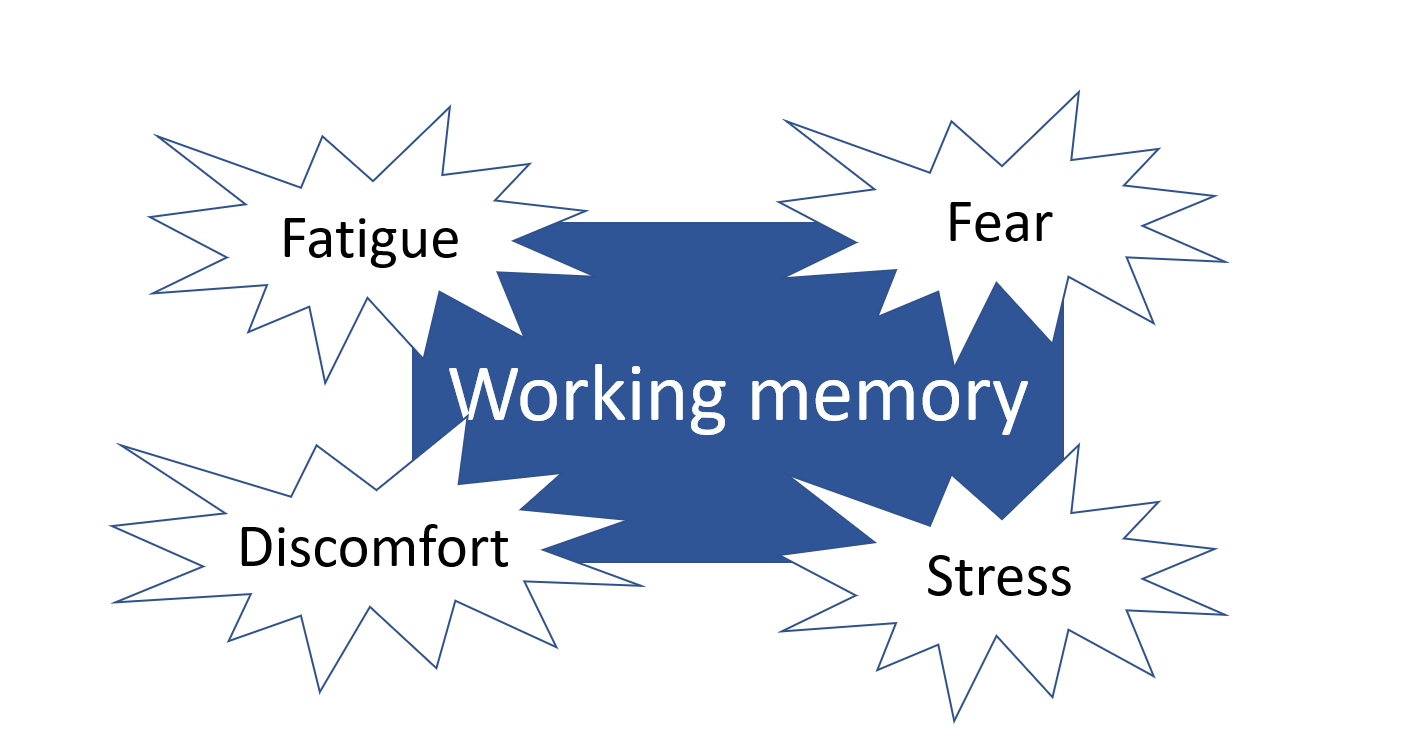

Working memory is quickly overloaded and fatigued. Stress about personal life circumstances, fear of being in a new learning situation, fatigue, hunger, even an uncomfortable chair or room temperature intrude into working memory resulting in less capacity for full concentration on the material being learned.

Mental attitude impacts your learning capacity in surprising ways. Meta-cognition—the way you think about your thinking—has an impact on information retention and processing even when the learner isn’t aware of it. Thinking that you cannot learn will have a negative impact on learning. Conversely, confidence that you can learn will have a positive impact on learning.

Mental attitude impacts your learning capacity in surprising ways. Meta-cognition—the way you think about your thinking—has an impact on information retention and processing even when the learner isn’t aware of it. Thinking that you cannot learn will have a negative impact on learning. Conversely, confidence that you can learn will have a positive impact on learning.

In one study a group of Asian women was recruited for a study. Researchers divided the women into three groups, all of which took a math test. Before the test, one group was quizzed with questions about their female gender. Another group was quizzed about their Asian heritage. The third (control) group did not have a quiz. The group that was quizzed about their Asian heritage did the best, the group quizzed about gender the worst.

Why? Researchers concluded that the group quizzed about their Asian heritage was influenced by the bias that Asians are smart at math. The group quizzed about gender was influenced by the bias that women are poor at math (completely false by the way). No one is immune to stereotypes and bias, even members of the class.

Studies about ageism or age bias suggest that older students may also under-perform in the classroom because of their inherent internal bias. As an instructor, keep in mind that you need to create an atmosphere of ease. Assure your students that no matter how long they have been out of the classroom or how new technology is to them, they can master the material and you will help them. No one gets left behind.

How do you facilitate real learning in the classroom? Have discussions about the topics of learning. Ask your students to relate the topic or compare the topic to something they already know. Ask them how they will use this new piece of knowledge in the future. Mere repetition is ineffective. What you are trying to do is get students to hold the item in working memory for a couple of minutes and relate it to things they know. This form of elaborative learning is the best way we know to form the new neural networks that make up permanent memory.

Cognitive load

You’ll hear me talk a lot about cognitive load. In simple terms, we can only attend to a limited amount of incoming information at any given time. After that, we are overloaded, and learning cannot happen. As an instructor, one of your prime directives is to make sure that your students are not overloaded, that they have time to process, and hopefully encode, information.

Fear

Before we even get to information overload, understand that fear, fear of failing, fear of being in a classroom again, fear of not understanding technology, terminology, or even English, contributes to cognitive load. Any part of your student’s minds that are attentive to fear cannot be attentive to the subject of learning. It is critical that you create a non-judgmental environment that nurtures learning. Make your students feel safe. Let them know that they will have the time and support that they need to be successful. Remind them that they have learned and mastered many things in their lives that are far harder and more complex than the material they will learn in class with you. This may mean that you need to encourage a special seating arrangement. Make sure that everyone can see and hear you and your presentational material. Depending on your classroom situation, you may even want to seat students so that they are with others in their age groups.

Terminology

Part of your job is to teach the necessary terminology. Students are going to face two language challenges: you will be teaching them new terms for which they have no associations, and you will be using words they know in unfamiliar ways. As an example, someone new to computers will not know what a central processing unit (CPU) or operating system (OS) is. These are new terms, and concepts, to them. You might also be teaching your students gestures, which is a term they will know, but not in the sense that they have known the term in the past. To them, gestures include waves and angry traffic encounters, not swipes, pinches, and taps. When learning something new, the challenge is to encode or commit the information to memory. When learning something new about something we already know, sometimes prior knowledge can actually inhibit learning the new information.

Pace

Understanding language, both spoken and written, is one of the most cognitively challenging tasks we ask of our brains. We must interpret the shapes of letters or decode sound waves, construct sentences and meanings, and then put it all into the context of what we already know about the world. This process takes measurable time, although we may think of it as being instantaneous. If one of your students is struggling with understanding something you said, or trying to make some sense of a new concept, they are unable to deal with new information and will fall behind. Stop to check in frequently with your audience. Ask if everyone gets it and encourage questions. Questions help everyone think more deeply about the information being discussed and therefore helps everyone more deeply encode the new knowledge.

Summary

As an instructor you need to be aware of the limitations of working memory and actively work to reduce distractions and reduce discomfort and stress. You should create an atmosphere that encourages relaxation and concentration and eliminates, as much as possible, students’ fears of speaking up when they have an issue. Relating the technical details of the class is often the easiest part, conducting the class in the most effective manner to facilitate concentration and learning is often the hardest.